Reflections 17th August

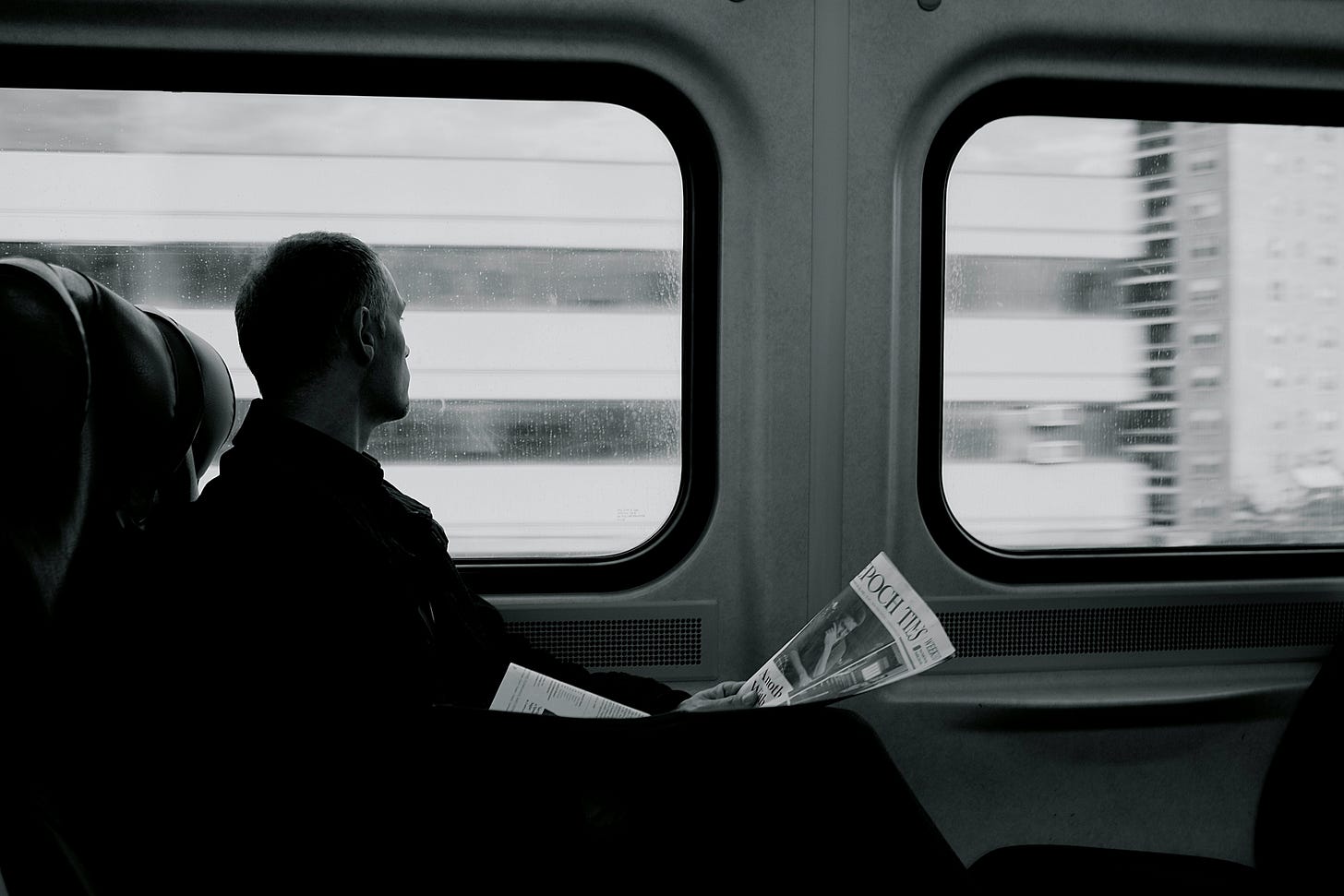

Thoughts on a train

Travelling is one of those things we don’t talk much about; it has become a largely invisible element of our lives.

I think that’s a shame. At its best, travelling to new places is one of life’s joys; at its worst, travelling to a “work theatre” meeting that could have been done on Zoom is dispiriting at best. According to the Association of Accounting Technicians, in an average career, we spend 557 continuous days, or one and a half years, simply in transit. And around £25 billion a year on rail transport, £4 billion on coach, and around £60 billion on road freight.

We spend close to £50 billion a year buying new cars. EVs were not created to save the environment. They were designed to save the car industry.

It seems we no longer travel out of necessity; we travel because it has become a market with us as consumers.

I Work, Therefore I Travel.

Commuting often promises higher pay but rarely delivers a true return. While longer commutes can bring wage premiums (notably for London roles),…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Outside the Walls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.