Reflections 9th June

Conversations as Journeys between Observation and Orientation

The journey between observation and orientation is a well-trodden path we travel many, many times a day. Connecting them is at the core of making the impact we want to, however small.

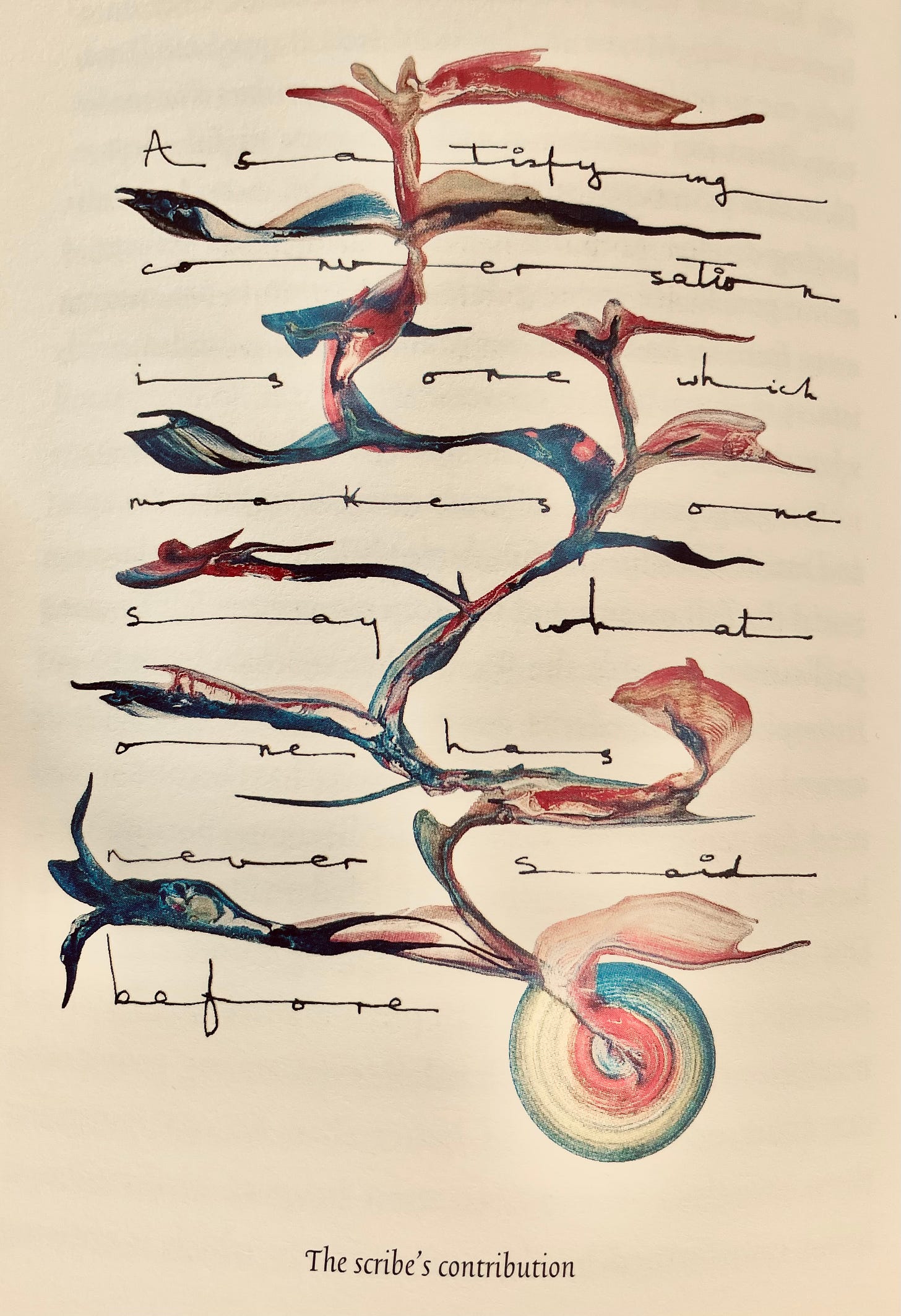

It is, as Zeldin points out, about saying what has never been said before.

A key feature of uncertainty is that there are no specialists. There are no qualifications. When complicated crosses the boundary into complexity and chaos, dealing with it is a contact sport. It involves constructing hypotheses, a willingness to be wrong, and being prepared to lead. It means being prepared to entertain scepticism regarding the tried and tested “evidence-based and proven” models in favour of experimentation, improvisation, and listening to the heretics, trespassers, poachers and pirates who live outside the walls.

This may be one reason our record of innovation in business and the public sector is far more focused on new processes and IP than new products. Our incidence of "innovation-active” businesses has fallen from 45% in 2018-2020 to 36% in 2020-2022. (Source: Nesta, UK Govt). We have preferred doing what we know how to do better rather than exploring new areas. We are focusing on turning heuristics into algorithms rather than exploring mysteries to generate heuristics.

It feels as though we are tending towards economic versions of the tricoteuses of the French Revolution, watching smaller innovative businesses being executed by our preference for safety.

Observing many of the posts and articles in the mainstream business press often feels like regifting. There is rarely much that is new, just things that have been said and written before, presented in different wrappings. Meetings have similar qualities. What is known and proven is preferred over the novel and unproven. Safe is better than risky. Mimesis carries the day. Nobody gets fired for hiring McKinsey, which probably says it all.

I asked perplexity.ai to look for evidence that lack of opportunity to pursue new ideas is a cause of people leaving businesses, and was surprised that the result was so clear. The sources are reasonable, and whilst a detailed appraisal of the data would require more “hands-on” work, it seems sufficient to support a hypothesis that organisations in pursuit of efficiency and productivity will lose the technical and attitudinal talent that can fuel the innovation they will require when the impact of diminishing marginal returns on efficiency and productivity make itself felt.

It raises an obvious observation. Where does that talent go, and where does it look for leadership?

Leadership is an area in business that is mentioned so often that it has become invisible. We spend billions yearly on “leadership training,” mostly without metrics to measure results. Leadership has become a course to be completed to get a tick in the “competencies” box and then forgotten about. It is easy to see why leadership has little scope to make an impact when our businesses are woven through with mandatory processes, protocols, and policies, and those doing the “leading” are measured on metrics that rely on hard data and short timescales.

Peter Drucker said, “Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast,” but where does Culture come from? In most organisations, leaders are not in place for long enough, nor do they have enough autonomy, to determine and direct culture. Culture is what’s left after the results have been delivered and the proceeds distributed.

Earlier this year, Forbes ran an article suggesting AIs could replace CEOs, a theme that is increasingly being picked up elsewhere. The idea is perhaps not as ludicrous as it sounds when we consider the common language and priorities most CEOs seem to use, and the prospective leap in capability of the next generation of AI. Perhaps MBA is increasingly becoming to represent “Meat-Based Algorithms,” and all the company needs to do is go vegan.

That is why I believe conversations will move centre stage. Human conversation (as opposed to its clever AI chatbot equivalent) cannot be automated. It does not follow predetermined paths and, with encouragement, ventures into areas that AI cannot—the future and the imaginary.

If you want to understand a culture, sit quietly somewhere and listen to the conversations going on in and around you. You will quickly understand that the conversations evidence the culture and provide leadership, not the “leaders” who, increasingly, only lead in the way that a train driver leads a train between stations.

It is conversations that bridge the gap between who we are as observers, how we observe, and the actions we take on what we see.

When faced with the same situation, you and I will see it differently, even if only in the slightest way. Our conversation, though, weaves these different observations into something far more robust than our own alone.

In more stable times, leaders were expected to know. In times of uncertainty, however, they are expected to enable us to journey and discover together.

Leaders today are containers for conversations. The quality of that leadership depends on their ability to chart the journey they want to take us on:

What destination do they have in mind? What sort of journey do they envisage? How well are we prepared and resourced for when things go wrong? Who do we need on the journey? How well are the team members connected to each other's histories and aspirations?

I want to explore these questions in the company of paid subscribers in this and future posts.

For those thinking of subscribing, I offer no answers or formulas, just frameworks for finding the questions that matter to us. The answers are down to each of us.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Outside the Walls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.