Reflections 6th July

Navigating Spaces - and the Nature of Probably

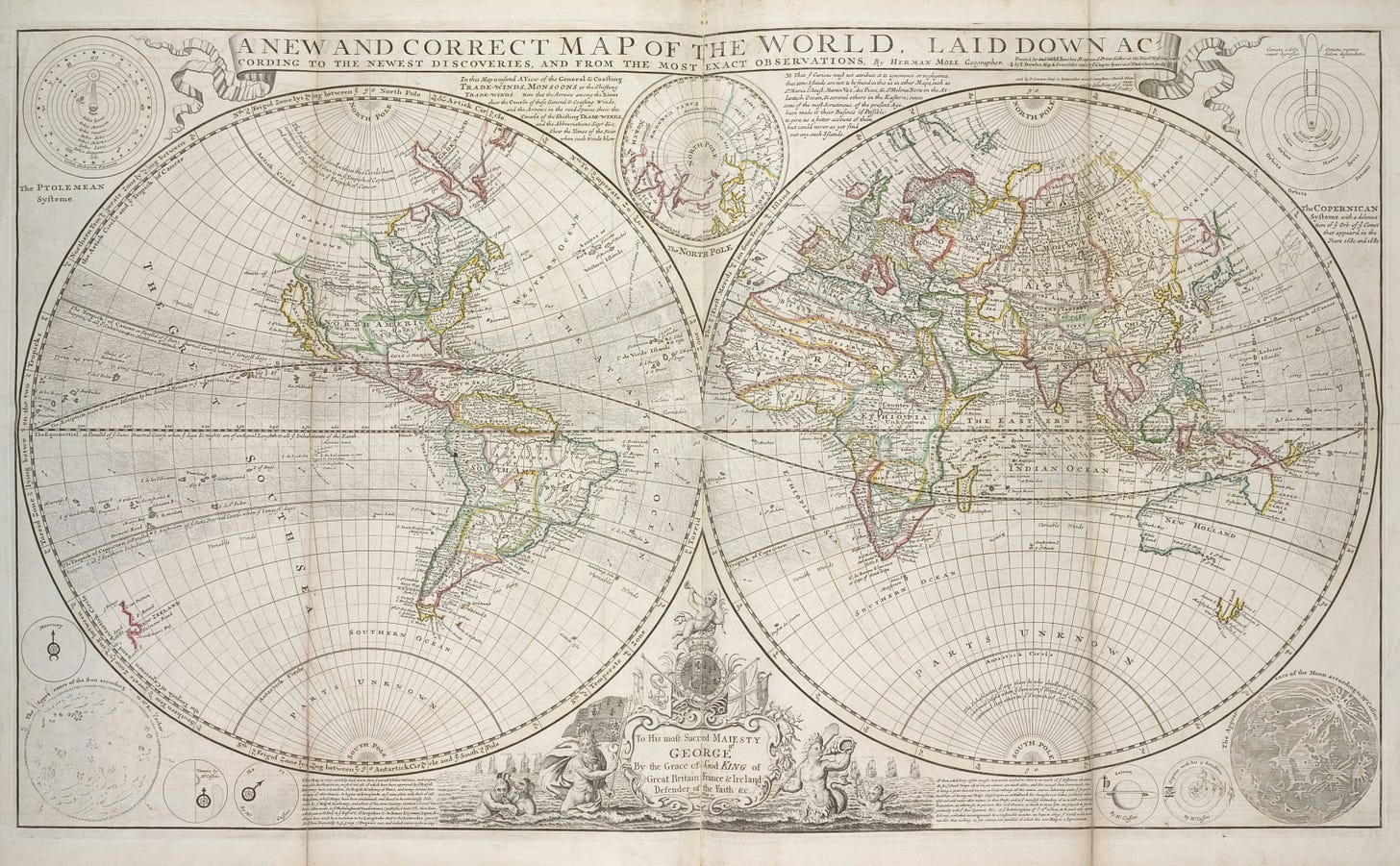

The idea of "spaces" is a constant companion at the moment as I watch organisations, assumptions and entire industries dissolving. They remind me of the ways we are now able to observe distant galaxies dying and being born, aware that what we are seeing happened millions or billions of years ago, and that we can do nothing about it.

All we can do is watch, wonder, learn, and prepare to navigate into the new spaces that are emerging.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Outside the Walls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.