Reflections 30th November

Navigation When The Ground Moves

Last week I wrote about a quiet insurgency; not a revolution of barricades and manifestos, but a shift in how we might choose to learn and grow. How, looking from the outside, we might circumvent institutional bottlenecks to form starfish networks of small communities of practice.

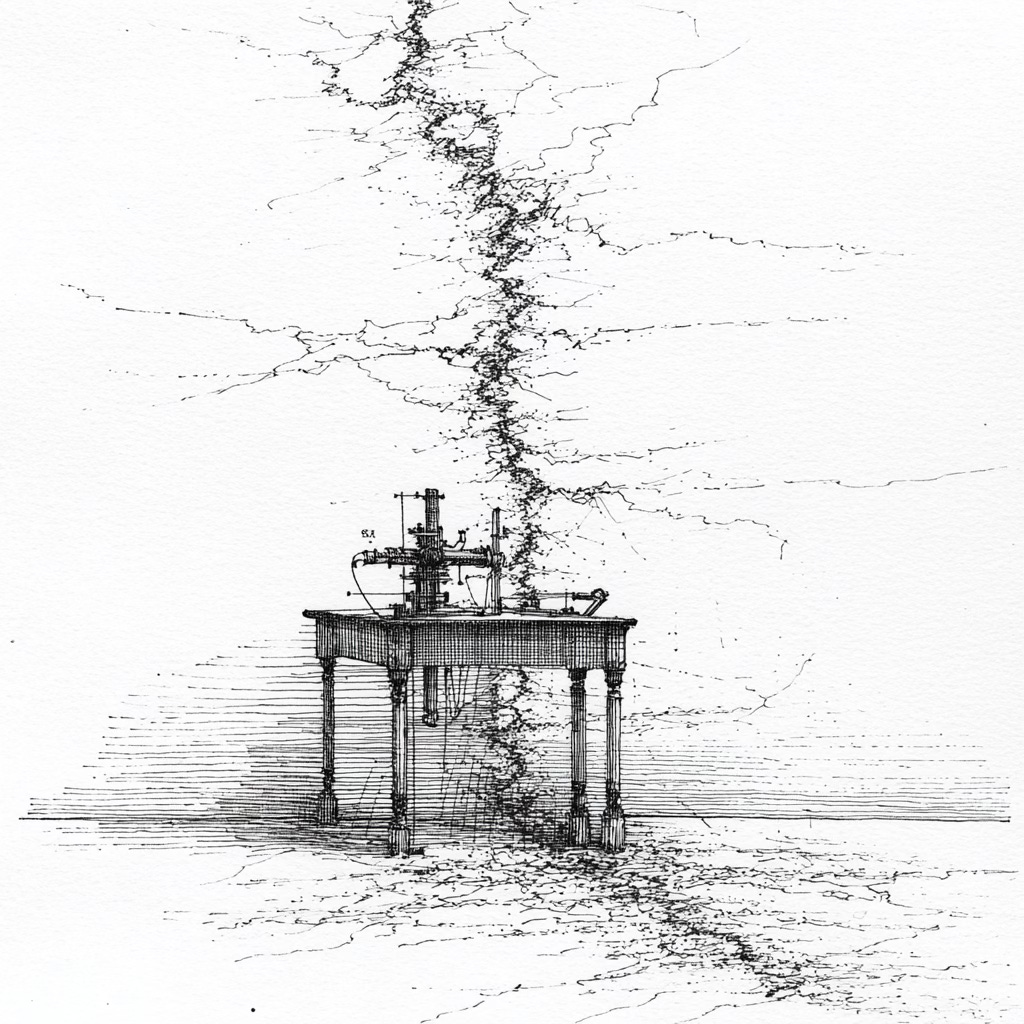

It raises a question that has been on my mind for a while, brought to front of mind by recent experience. If conventional structures no longer serve as reliable guides for development, what compass do we insurgents use to navigate?

When the land moves beneath us, we need different tools. Our reaction has to move from the paralysis of “Oh S**t” to “that’s interesting,” and our attention must shift from looking for escape routes to noticing just what is changing around us.

When Maps Become Fiction

The maps we create are partial; they show us the topography, but not the geology. We may be aware of the tectonic plates …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Outside the Walls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.