Reflections 28th September.

Shifting Sands

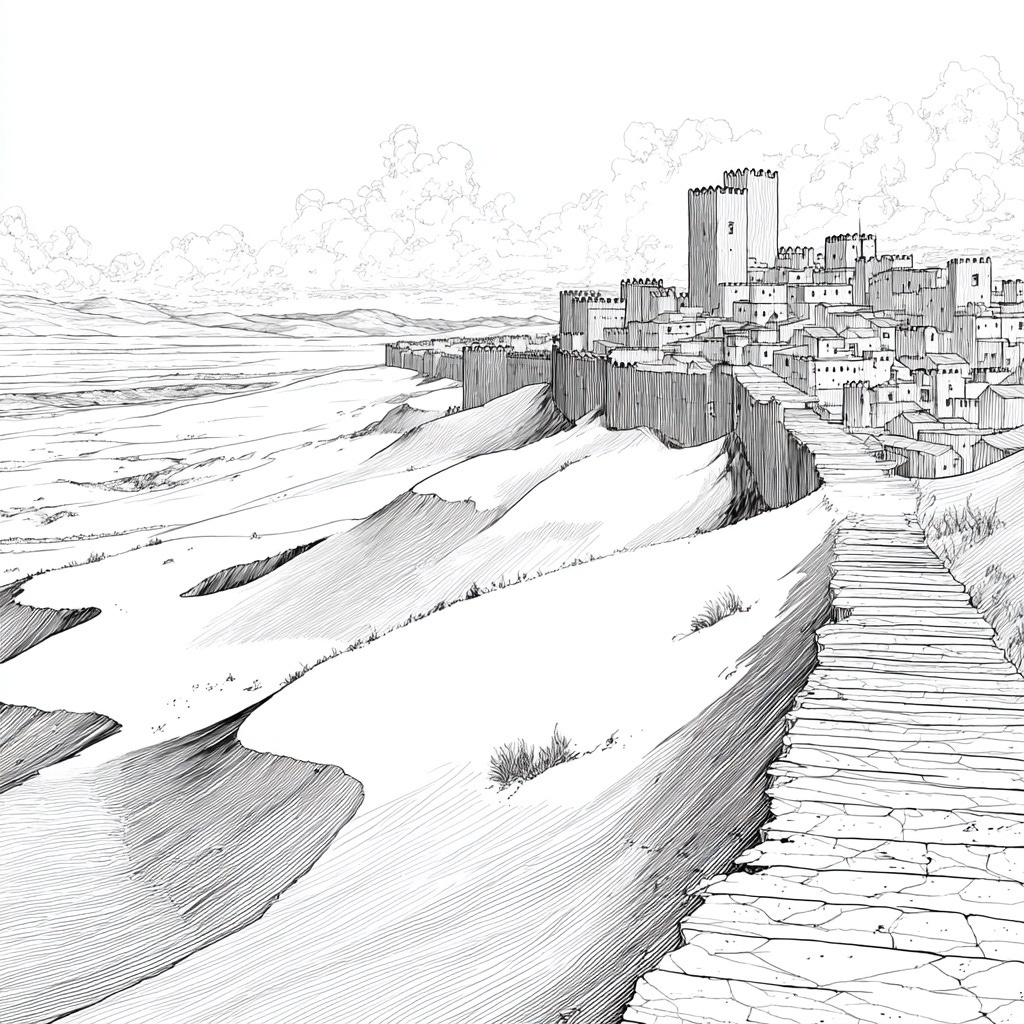

Walls are such satisfying things in many ways: the implied permanence, the sense of security and safety. They are tangible. We can lean on them, shelter behind them and take comfort in their existence from a distance.

The challenge is that we can become wilfully blind to their nature: who they keep inside, who they consign to the outside, who builds them and who owns them. Who they offer security to, and whether they are actually keeping us safe or keeping us prisoners. Left unattended, walls ossify. They cease to serve and become instruments of power.

In recent posts, I’ve found myself leaning more towards organic metaphors: sandbars, tides, skies, and other things antithetical to walls. Boundaries in nature are not fixed perimeters; they are places of transaction. The notion that a line should be impenetrable is a human contrivance.

Much of today’s narrative is cast in the language of chaos. Whether AI is a bubble, whether it will take jobs, whether it wi…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Outside the Walls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.