Reflections 1st February

On Toast

Have you ever done that thing where you turn up at a party in fancy dress to find everybody else in dinner suits? Or perhaps the other way round? That’s what it feels like at the moment, talking to a lot of people about the changes that we’re facing, whether the subject is AI, wider technology, the changes in geopolitics, climate change, or quite often an exotic cocktail of all of them.

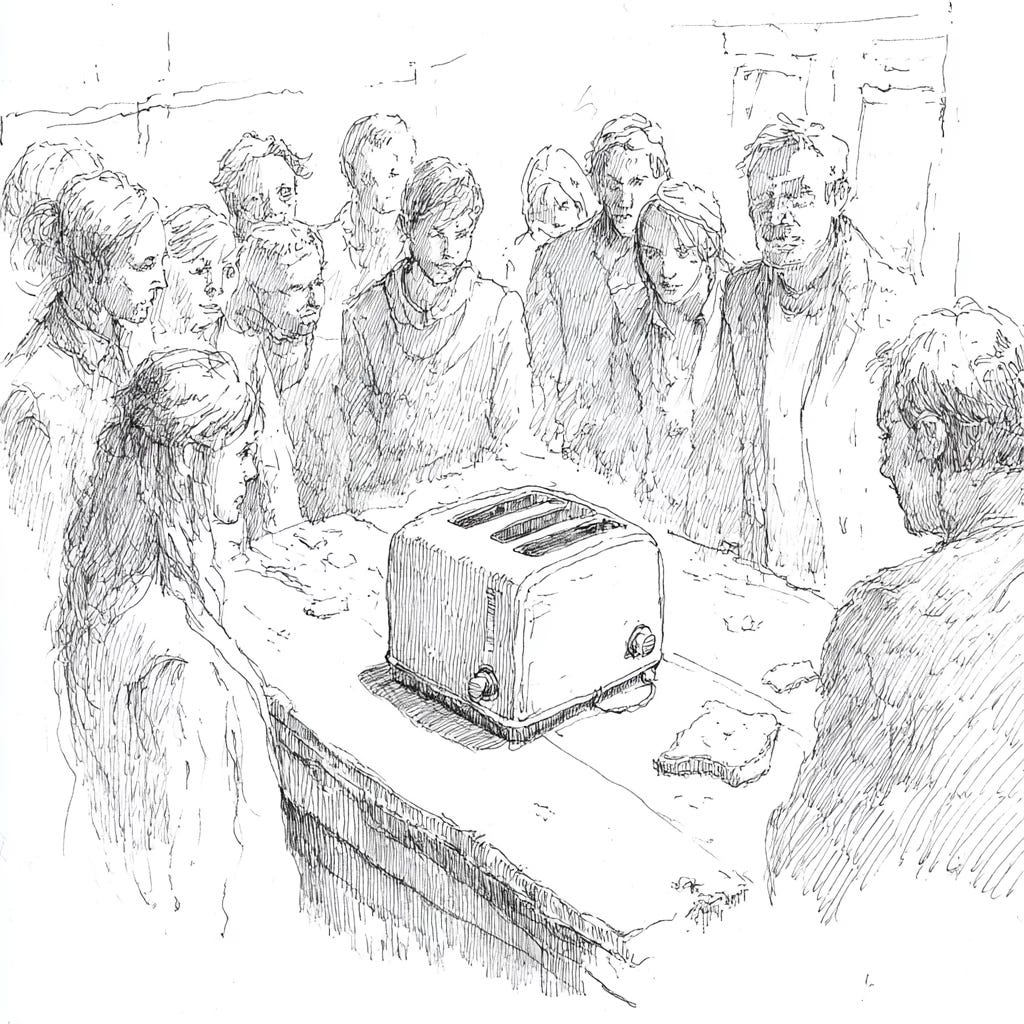

The conversation about how we must adapt, change our business model, and get new qualifications. Cuddling the comfort blanket, hoping that, if we do, when the current turbulence subsides, we’ll be fine on the other side of it. Then we get to the part of the conversation where we recognise that the things we’ve been used to having as building blocks to create our careers are toast.

That is when the conversation really starts.

Most of the time, these conversations are with people who want to have them but don’t know where to start. The conversations are uncomfortable at first, but people are prepared for them, a little like going to the dentist. Sometimes, though, they arrive out of left field, and those conversations are really interesting.

I found myself in one such this week. I took our car in for a service, one of those “while you wait” exercises, conducted at a very smart, shiny German dealership where the cars are forty per cent function and sixty per cent ego, portraying the ability to do things on the open road that suggest freedom and status, but that are guaranteed to get you arrested if you try. Like many, we’re at a point where we’re looking to move away from internal combustion to electric, and being a largely captive audience for a couple of hours while I waited, I found myself in conversation with somebody from sales. We got into a left-field, interesting conversation.

EVs seem to fall into two broad categories at the moment. There are those being offered by brands with a long history in automotive, steeped in internal combustion philosophy and drivetrains. Then there are those with an entirely different history, new on the scene, who are designing EVs like they design computers, often using people with similar backgrounds.

The petrolheads, of which I am one, are having to get to grips with a new reality. It feels a bit like taking the ecological equivalent of Mounjaro. We know we’ve got to lose weight, but we need assistance, even as we look longingly at the things that we know we can no longer have. The legacy brands try to make us feel better about it, offering us cars that look the same, which they say are imbued with the same qualities, but shoehorning electric drivetrains to replace internal combustion engines. It’s an uncomfortable fit and evokes a sense of the uncanny valley.

They trying to convince us that it’s the same, but it’s not. That of itself is not a problem, it’s the absence of an alternative story. The companies themselves carry a long history based on a paradigm that no longer applies, and nobody has told them their history no longer matters. Their DNA reeks of internal combustion engines, the freedom of the road, and all the other things that the advertising agencies made their money on. It carries a significant legacy cost, both financial and cultural. They find themselves somewhere they did not initiate, do not really understand, wearing the weak smile of false hope.

The new entrants find themselves, on the one hand, with no sacred cows to slaughter, and, on the other, a reputation to build have a freedom that gives them a huge advantage. They can create the automotive world anew, not struggle to adapt. They are probably best exemplified by Tesla, where Elon Musk used his undoubted genius to really disrupt the market. The fact that he’s then shot himself in the foot through his personal antics, incompatible with a consumer brand (or humans in general) is secondary. He has shown the way, and many organisations are ready, able, and willing to follow.

Next door to the shiny dealership I was sat in were two of the new Chinese brands with vehicles in them that, to all practical intent and purposes, are indistinguishable from the ones in the showroom I occupied. The difference is that they are half the price, with longer warranties, and the energy of new kids on the block. Yes, they are currently something of an unknown quantity, but that is changing rapidly. They are interesting. It remains true that if you want to do some serious heavy lifting or cross-country work, a Land Rover is the vehicle of choice. If, on the other hand, what you want to do is have a lot of space to lug the family around in an urban environment, a Jaecoo or BYD will do all of that and leave you £60,000 over with which to nurse your ego.

The conversation made me smile. The person I was talking with. was bright and personable with no illusions. He will have no problem making the transition to the new reality. He doesn’t need an over priced product to build a client relationship, and could move next door without missing a beat. He recognised the issues as much as anybody and regards following the instructions he is being given to sell stories he doesn’t believe as a short-term necessity. He was mētis in action: that practiced ability to read the situation, see through the organisational theatre, and navigate accordingly. I suspect there are very many more in every sector just like him.

This, of course, is just the beginning. A conventional car has hundreds of moving parts, relies on explosive fluids and regular servicing. An EV has less than twenty moving parts, and much less maintenance, much of which can be done remotely. So much for shiny service centres.

Later in the year, we’re going to see Waymo cars in London. If you’re a black cab driver, adapting to that over the medium term is a serious rethink, probably involving neither black cabs nor the Knowledge as you’ve understood it.

It’s not too big a leap to look at our organisations in most sectors and recognise the same issues. If you’re looking to integrate AI into your business model, you’re missing the point. AI may be able to make the things that you make at a lower cost, but the work of connecting to the people who use it and buy it requires a different set of skills altogether, involving capabilities that are totally foreign to algorithms.

Whether we talk about this in terms of alchemy at The Athanor or craft at New Artisans, the message is the same: it’s not about adapting, it’s about phase change. This isn’t refining what exists but recognising fundamental structural transformation.

I came across a framework this week that clearly captures this shift. At its heart is the idea that:

The unit of value shifts from what is delivered to what the customer can now do.

The producer moves into customer space, supplying not just an offering, but scaffolding: tools, workflows, integrations, guidance, and sometimes embedded expertise.

Durable advantage comes from customer compounding. As customers become more capable, their ambitions expand, their usage deepens, and the relationship becomes harder to unwind.

Source below: - well worth reading, and the follow-up posts.

This captures what I’ve been writing about in terms of mētis and craft: putting the human at the centre of the creative process, not as some add-on to an algorithm. It reminds us of boundaries and that we cross them far more easily and elegantly than algorithms ever will. The car salesman reading the potential client, the black cab driver who provides context and knows which route to take based on time of day and weather, and the designer who senses what a client needs before they can articulate it offer capabilities that compound in ways no algorithm can replicate.

Used well by humans, AI will do to legacy businesses what EVs are doing to internal combustion engines. The organisations built around the old paradigm will find themselves trying to shoehorn new technology they are uncomfortable with into old structures that cannot handle the power.

The challenge is for us to believe in ourselves; to trust our own capabilities rather than the stories we’re being told about adaptation and retraining. To recognise that which we already possess: practised judgment, an ability to read situations, improvise and the capacity for genuine transformation. These things don’t become obsolete; they become more valuable precisely because they can’t be “algorithmed”.

There’s a great opportunity here to find the language that we need. I find that when I’m trying to explain this space to people in the language that we normally use, it doesn’t work. If we use traditional language, people think in traditional frameworks. Those who create the language create the stories.

We need a new language for this time, and my focus for that is The Athanor. Creating a language of work to replace the one that is obsolete is not a matter of logic and science, it is one of craft and alchemy.

And we need to do it now, because legacy organisations will become toast far faster than we will.

We need to be ready.