Reflections 15th February

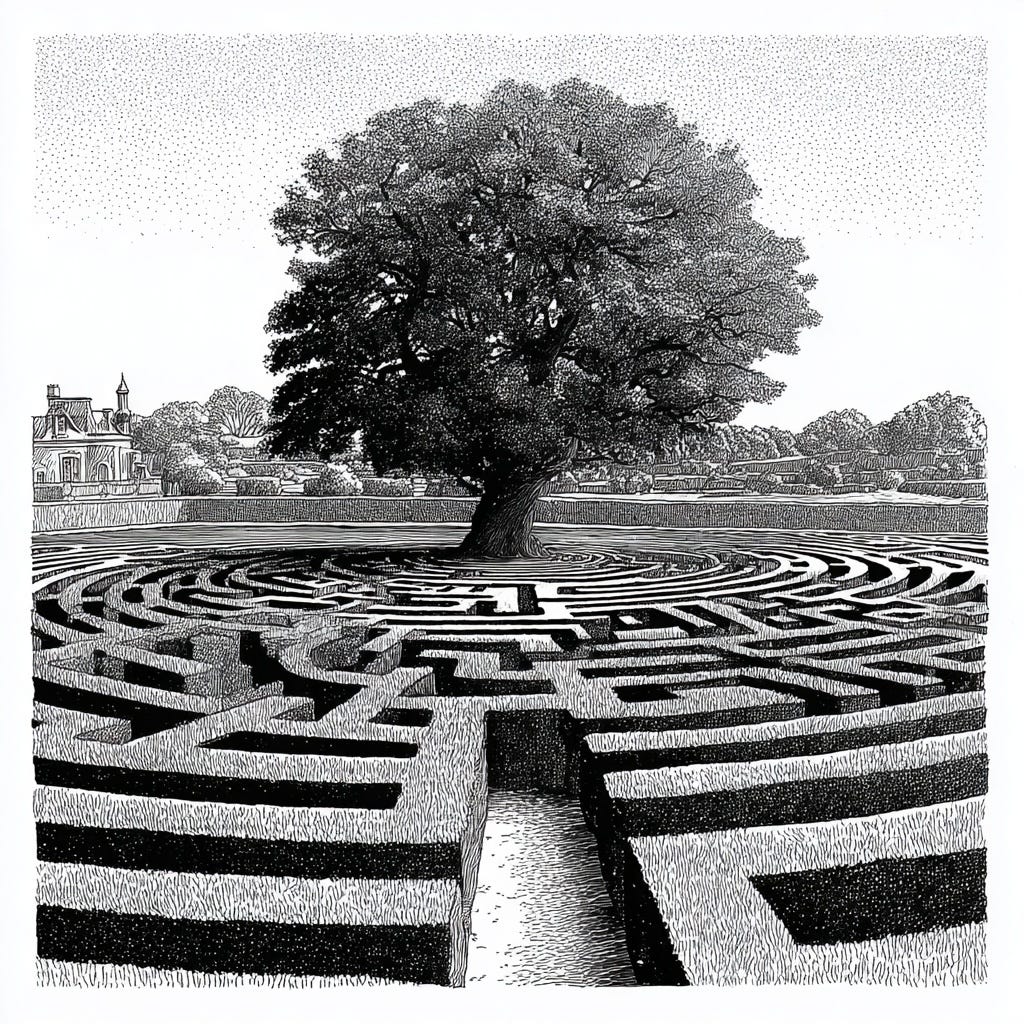

Going Round in Circles, Finding First Principles.

Going Round in Circles?

There are places precious to us, woven into childhood memory. Their contours, their smells, their textures become part of who we are, and returning decades later to find them transformed into executive estates and industrial parks is a shock, indistinguishable from every other development, with personalities reduced to postcodes. Our ancestors must have felt something similar when enclosure acts turned common land into private property. We become strangers in what once felt familiar.

Now the same thing is happening to our skills and knowledge.

Capabilities we thought were ours, protected by qualifications and professional memberships, are being taken and offered for monthly subscription to anyone willing to pay. This is the price of an education that prioritises answering questions without spending time creating them. Graded responses to approved questions, recognised by certificate. Commodities designed for an industrial economy that no longer exists in the form it did when our education policies were created.

We need to move beyond approved questions.

I sense we’re going round in circles; lots of energy, little forward motion. Endless articles about the nature of work, AI’s impact, whether artificial general intelligence will arrive, and whether the whole thing is a bubble. Meanwhile, what’s been unleashed cannot be undone. The technological toothpaste will not go back in the tube.

So, this week I asked myself whether I’m in danger of going round in circles too. I asked Claude to analyse all my writing across three blogs, from their start, identifying emergent ideas versus creative reassembly of existing ones. Nearly 2000 posts. The answer was salutary. Not circling, but spiralling upward, but approaching saturation. I know the process is mathematical, but it resonated.

What I need now, for a while at least, is fewer new ideas and more demonstration. Less elaboration, more evidence. Stop describing, start proving. Consolidation and demonstration, not further exploration.

Why We Circle

We’re circling because we’re stuck in what C. Thi Nguyen calls “achievement play’.

Every article asks outcome questions. Will AI take jobs? Will it create wealth? Will it concentrate power? These treat AI as a problem to be solved, a test to be passed, a competition to be won. We’ve reduced everything to winning and losing, to capture and scale, to efficiency and productivity. Pure outcomes.

But what if the question isn’t whether AI makes us winners or losers, but what kind of engagement it enables? Not what it achieves for us, but what it lets us strive toward?

This requires a different frame entirely.

The professionals whose skills are being commodified aren’t just losing income, they’re losing their structure of valuing. The tax specialist cares about regulatory minutiae not cynically but genuinely. They’ve been shaped by the game they learned to play. When AI does tax preparation, it doesn’t just threaten their livelihood, it makes obsolete an entire way of caring about the world.

This is what makes AI disorienting beyond economics. It doesn’t just automate tasks. It renders meaningless the distinctions we’ve learned to value.

Systems accumulate complexity like sediment. Each new rule responds to a specific case, each procedure to a particular failure, each requirement to someone’s concern. Rarely does anyone ask what might be removed. The result is a ratchet that only turns one way; towards greater complexity, and with it, greater dependence on those who can navigate the maze.

This matters because complexity transfers power.

When systems become too intricate to understand, people lose agency. They cannot act without expert guidance. Tax codes require accountants. Healthcare billing needs specialists. Financial products demand intermediaries. Building regulations favour large developers who can afford compliance departments. At each layer, someone extracts value simply from knowing the terrain.

Not all complexity is equal, though. Some reflects reality’s genuine texture. Brain surgery is complex because brains are complex, and climate modelling because climate systems are complex, and this intrinsic complexity cannot be wished away. The question is always about the gap between what’s irreducible and what actually exists. That gap reveals where power has embedded itself in complication.

History shows that progress often comes from reconceiving complex systems in simpler terms.

Newton’s three laws replaced Ptolemaic epicycles. The web succeeded partly because HTTP and HTML were simple enough for anyone to publish. Southwest Airlines stripped flying to essentials and revolutionised the global industry. These weren’t just aesthetic choices but power redistributions achieved through simplification.

When something is made simpler, capability spreads. Movable type and vernacular translation broke the Church’s monopoly on Scripture. Double-entry bookkeeping enabled trade expansion. Mobile money services bypassed traditional banking complexity to serve the unbanked. What was previously possible only for specialists becomes accessible to many.

This is why simplification faces such resistance. It threatens those whose position depends on complexity.

Finding Bedrock

There is an art in finding bedrock; the point where further simplification loses essential truth. Einstein’s principle applies: everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.

This requires distinguishing between complexity that serves the system’s purpose and complexity that serves those who administer it. The resistance to simplification reveals precisely where this distinction matters most.

The real distinction isn’t between needed and parasitic specialists. It’s between specialists who simplify and specialists who complexify. Brain surgeons create clear protocols from complex anatomy. Good teachers make difficult subjects learnable. The best engineers build simple interfaces to complex systems.

The rentiers are those who maintain complexity to preserve their position. Who profit from confusion rather than resolve it.

The question for any specialist work is this: does mastering it develop transferable capacity, or only facility within this particular maze? The surgeon’s knowledge transfers to new procedures, new technologies. The compliance officer’s knowledge of last year’s regulations transfers nowhere. One engages intrinsic complexity, the other parasitic complexity.

The question, then, isn’t whether to use AI but whether using it develops us or diminishes us. AI forces a choice into focus. It’s extraordinarily good at achievement play. Optimising, maximising, finding edges. It’s utterly incapable of striving play. Finding meaning in struggle, valuing process, caring about how something is done beyond whether it achieves the goal.

AI does not understand the craft ethic.

The danger isn’t that AI replaces us. It’s that in competing with it, we reduce ourselves to achievement players, and start valuing only what AI can measure.

A Different Game

Business is a game we invented. We set the parameters, and define what winning means.

Currently we’ve chosen profit, stock price, dividends and the primacy of money. We could choose contribution to community, human flourishing, and craft excellence. Both are valid games. The question is which game is worth playing well, and which structures of value we want to adopt, even temporarily.

Our business language has become functional and ugly because we’ve reduced it to achievement play, but it doesn’t have to be this way. If we choose to simplify it, we can see it clearly. We can choose the rules, the definitions of winning and losing. We can design for striving rather than merely achieving.

This is what makes stopping to examine what we have so important.

Exploration is enjoyable, but it can become avoidance of dealing with what we’ve found. Sometimes we must stop and make camp. Thoreau wrote that it’s not what we look at that matters, it’s what we see. For me, for now, it’s time to stop collecting and look carefully at what I have. To examine it from different angles, play with it, see what’s hiding in plain sight.

Time to stop writing about alchemy and practice some.

What Demonstration Requires

The Athanor must prove that there’s a different game available. Not by describing it but by playing it. Not by adding another framework but by creating space where people can encounter what matters beyond outcomes.

This means working with those in real organisations facing real uncertainty. Not teaching them to navigate complexity but helping them find bedrock, nor adding tools but removing obstacles. Not managing change but creating conditions where change can emerge.

The test is simple: do people leave more capable of engaging with reality, or only more capable of navigating our system? Simplifiers or complexifiers. Craftspeople or optimisers. Striving or achieving.

Periodic simplification back to first principles acts as creative destruction. Napoleon’s Code Civil replaced centuries of feudal legal complexity with clear, accessible principles. The Reformation asserted the priesthood of all believers against institutional intermediation. The personal computer revolution made computing accessible by simplifying the interface. Each simplified not by dumbing down but by achieving clarity about what’s essential.

Progress requires periodic return to first principles. The forces that resist this simplification show us exactly where value extraction has replaced value creation.

Today, we need value creation more than ever, before the value we have already created becomes exhausted.

So my work will shift for the coming months. More time into The Athanor. I’ll continue writing here and at New Artisans, but more as observation than analysis, until The Athanor yields something useful for our situation, individual and collective.

Stop describing. Start proving.

I’m looking forward to it.