Reflections 14th September

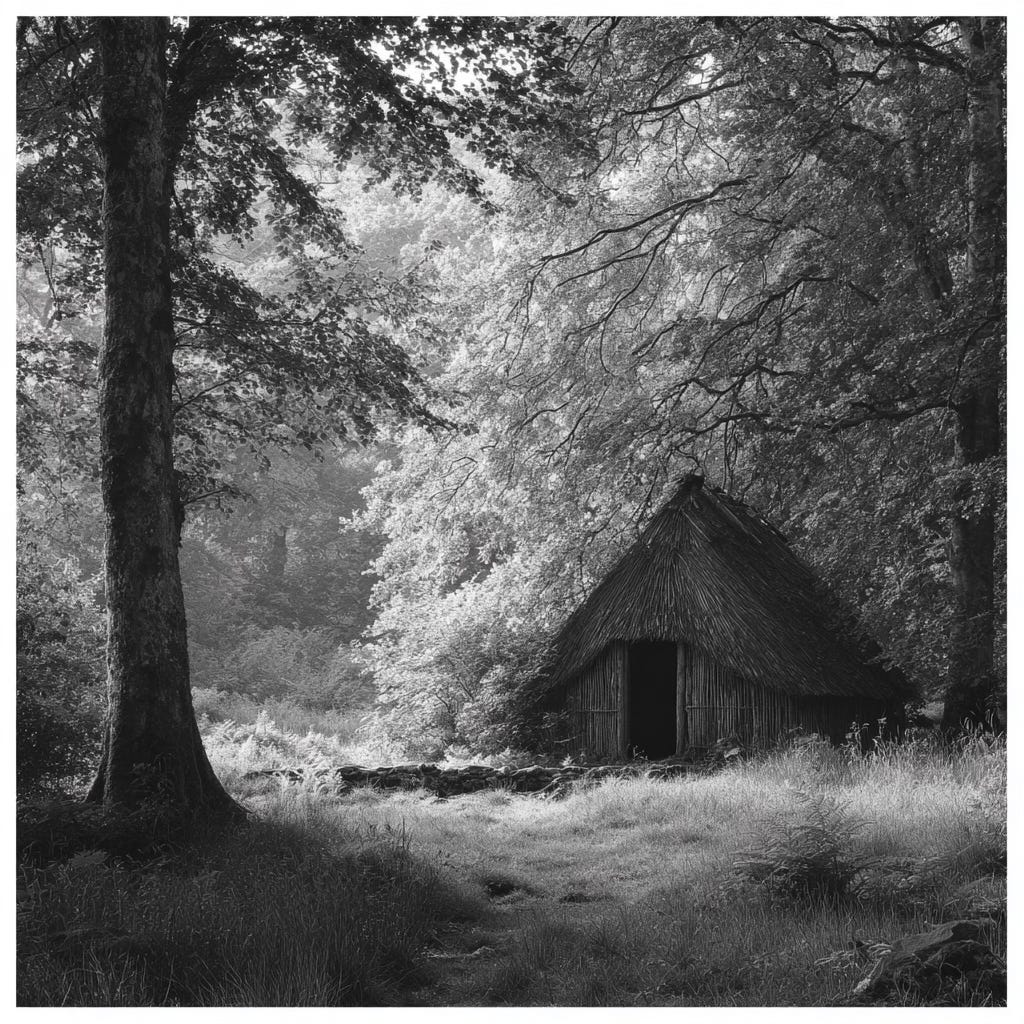

Something about Sanctuary

Violence today, no matter its form, is never just an act but a performance. When words fail, violence feeds the spectacle; its power lies less in the harm it causes than in how it is staged, shared, and consumed as part of the “real.”

“If you’re not confused, you’re not paying attention.”

Murphy’s Law of Combat (Vietnam Era)

The opposite is also true: If you are paying attention, you are most likely confused, and if you are confused, you’re an easy target for the unscrupulous.

The creation and exploitation of confusion has become, sadly, the default business model of not just social media, but anywhere negotiation has leverage. There is little profit in certainty.

Power often lies in arbitrage, exploiting gaps in what people know. Those with asymmetric information can move faster, frame narratives, and extract advantage before others catch up. Like financial traders, they profit only while the gap lasts; once the information spreads, the opportunity closes, a…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Outside the Walls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.