Reflections 12th October

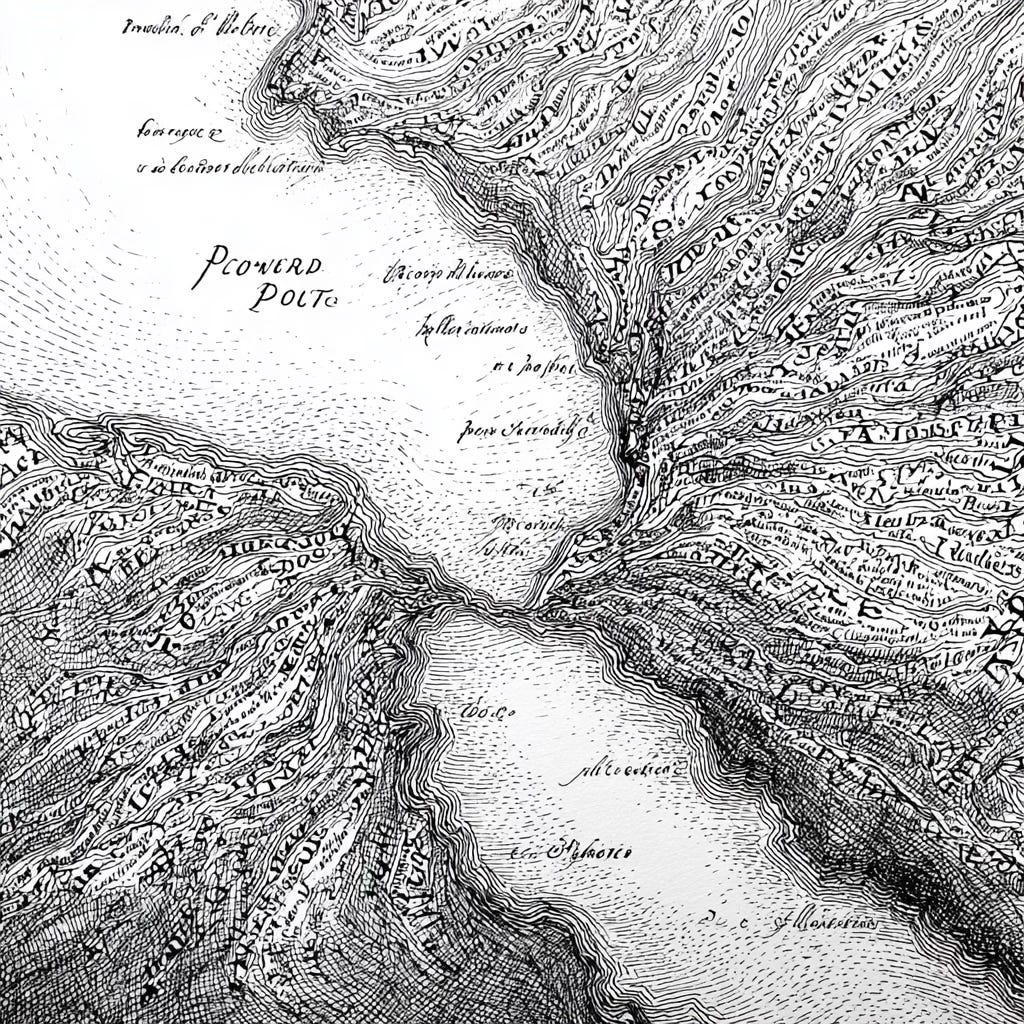

The Boundaries of Language

There are moments when the pace of change feels faster than our capacity to describe it.

Strategy accelerates, politics fragments, and perception tilts under the increasing weight of noise. Each domain, expanded and clouded by AI, invents its own language to keep up; words to contain uncertainty, frameworks to simulate control and yet these languages, once designed to clarify, now seem to multiply confusion.

Ever more desperate to be seen, the corporate CEO, the entrepreneur, the politician, the citizen, the scientist, the brand, each speaks fluently in their own idiom but struggles to make sense of or to understand the others. Each becomes fixated on their own truth and volume substitutes for dialogue.

We live in a new Tower of Babel, not of divine punishment, but of self-interested specialisation, wilful blindness and the resultant complexity.

However, the apparent chaos of this fragmentation carries opportunit…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Outside the Walls to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.